Quick! How many days did it rain on Noah?

Answer: It’s complicated.

Everyone knows that it rained for forty days and forty nights (Gen. 7:4, 12, 17). But then something unexpected happens: The waters rise for another 150 days (Gen. 7:24), from the 17th day of the second month (Gen. 7:11) to the 17th day of the seventh month (Gen.8:4) (using 30-day Egyptian months rather than Babylonian lunar months). Then the waters go down until the first day of the tenth month (73 days), when mountaintops appear.

Then forty more days pass (Gen. 8:6) before Noah opens a window on the ark, though without any mention of what month it is. Are we supposed to take this as an additional forty days after the appearance of the mountaintops (thus, the tenth day of the eleventh month)? What’s more, Noah lets out a raven, which never returns, then a dove, which does (Gen. 8:7-9); he waits seven days, releases the dove again, and again it returns (Gen. 8:10); he waits another seven days and releases the dove one last time, and it does not return (Gen. 8:12). That’s 54 days after the first day of the tenth month, or the 24th day of the eleventh month.

If you’re playing the “Holy Writ contains no contradictions” game, I think this is how you have to read it. And there’s nothing in the text that says you can’t. The next time the narrator tells us what day it is, it’s the first day of the first month of the following year (36 days after the dove doesn’t return, or 41 if the additional five days at the end of the Egyptian calendar are included), when the waters have receded but the earth is still wet. Then on the twenty-seventh day of the second month, the earth is dry (Gen. 8:14).

So this isn’t a contradiction in the sense that those Proverbs 26:4-5 were; the dates can all be set out in a row with no overlap. You have to read God’s speech in Gen. 7:4 to mean it will rain “at least 40 days,” which is a peculiar way of putting it, but not an instance of A/Not-A. If “God wanted to do it that way” satisfies you, have at it. You can take the rest of the day off.

So who’s still here? Yeah, it’s weird, right? Why is there sometimes a month and sometimes not? Was the ancient author just careless? Not at all. The Flood Story is one of the most carefully constructed passages in the whole Bible (Jewish or Christian). It is, in fact, a combination of two originally distinct versions of Noah’s story. And you can see how, by a simple experiment anyone can do at home.

Copy the text of Gen. 6:5-9:17 into a new document, or photocopy it. You can use any reasonably literal translation you like: I recommend the KJV, the NRSV, the NJPS Tanakh, or the NIV. Paraphrases like The Message, the Good News Bible and the New English Bible may or may not work for this, because they are willing to significantly change the text to suit their theology. So stick to a literal translation (I use the NRSV below).

Pick two highlighter colors. I’m going to use yellow and blue, but so long as they’re easy to tell apart, anything will work.

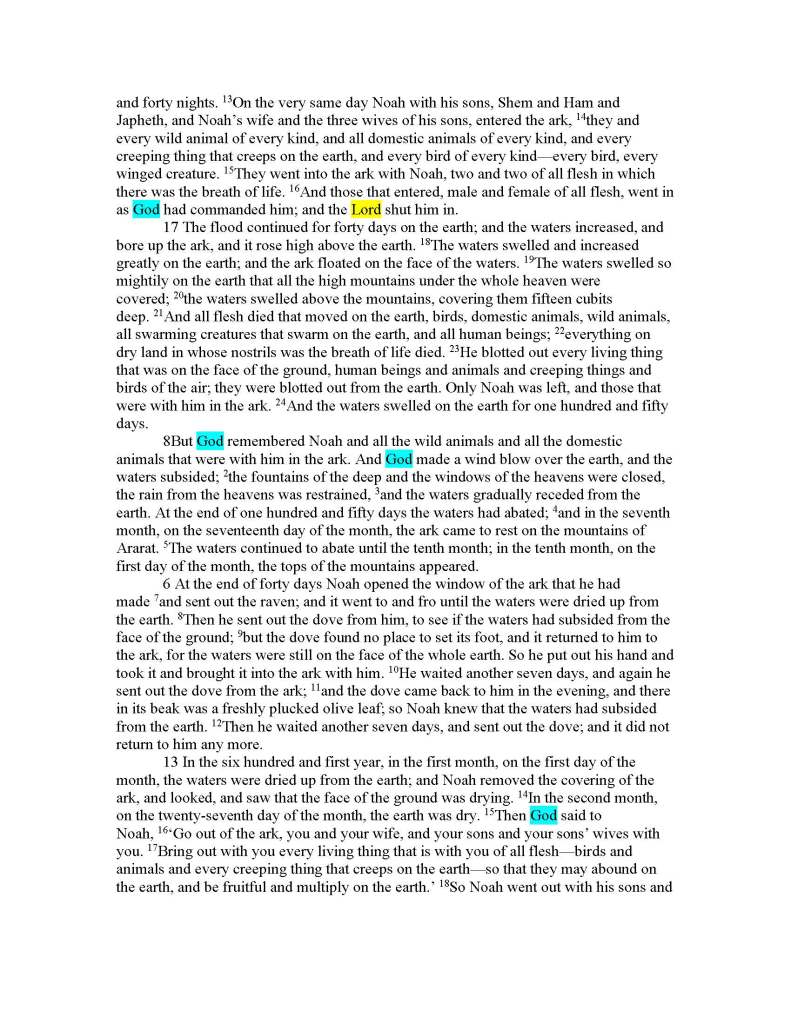

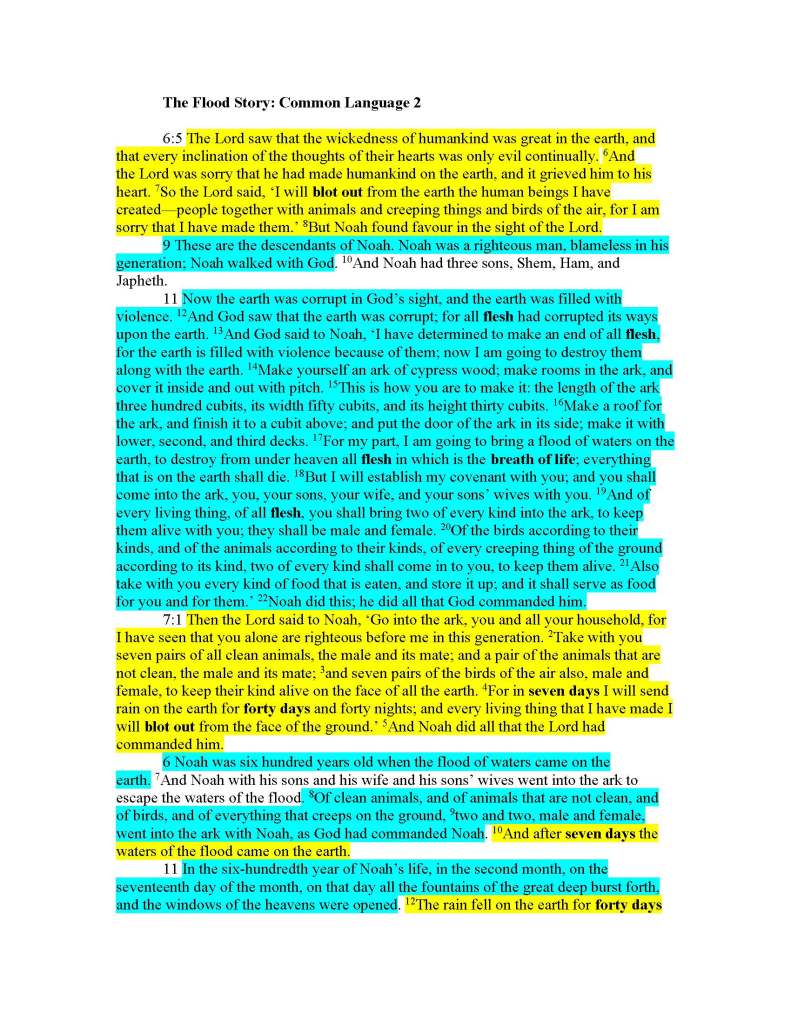

In color A (yellow for me), highlight the words “the Lord” every time they occur. Then in color B (blue for me), highlight each occurrence of the word “God.” You may never have noticed that the Bible uses different names for God. Maybe it doesn’t mean anything. Maybe it’s random. If it’s random, this experiment won’t work. Let’s find out. Here is my version of the passage so far:

Notice anything? It’s interesting that only one paragraph has both “the Lord” and “God” in it (indeed, in the same verse). But then, the paragraphs are not in the ancient Hebrew manuscripts we have; those are medieval innovations. And modern translators can break paragraphs at different points, so again, maybe it doesn’t mean anything.

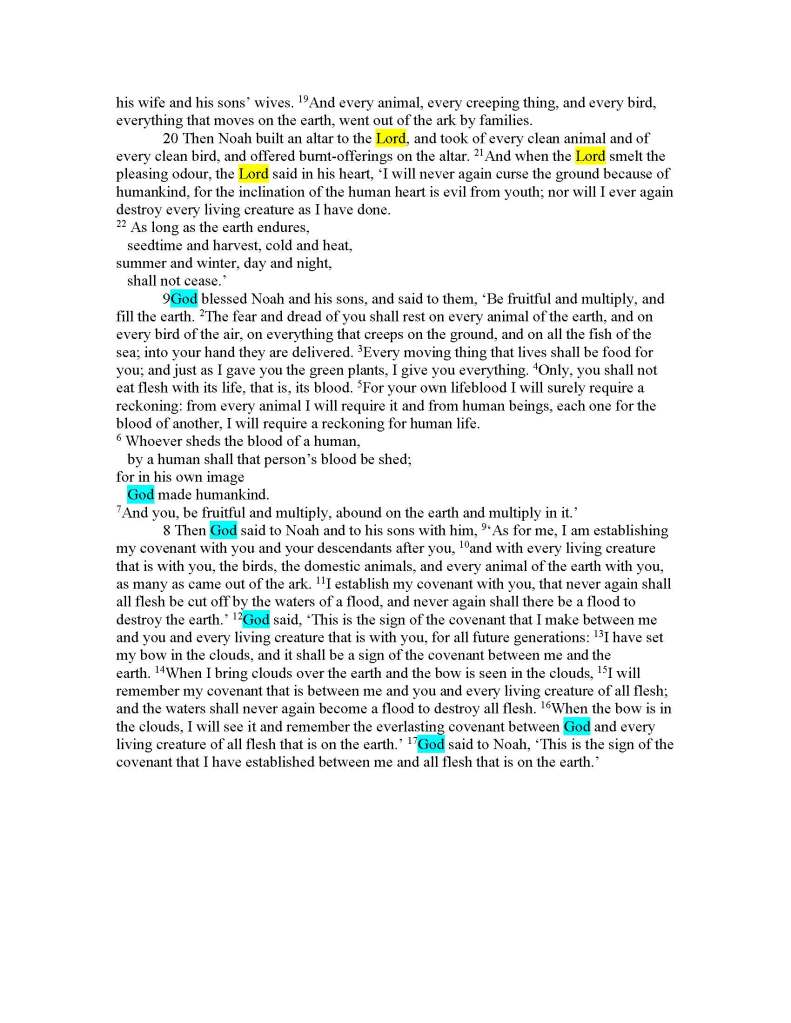

Let’s take a second step. Let’s expand our highlighting to include each whole verse in which “the Lord” (yellow) or “God” (blue) occurs. This does mean that Gen. 7:16 will two colors, one for the first part of the verse and one for the second. But just as the paragraphs are medieval, so are the verses. There are no verse divisions in ancient Hebrew manuscripts.

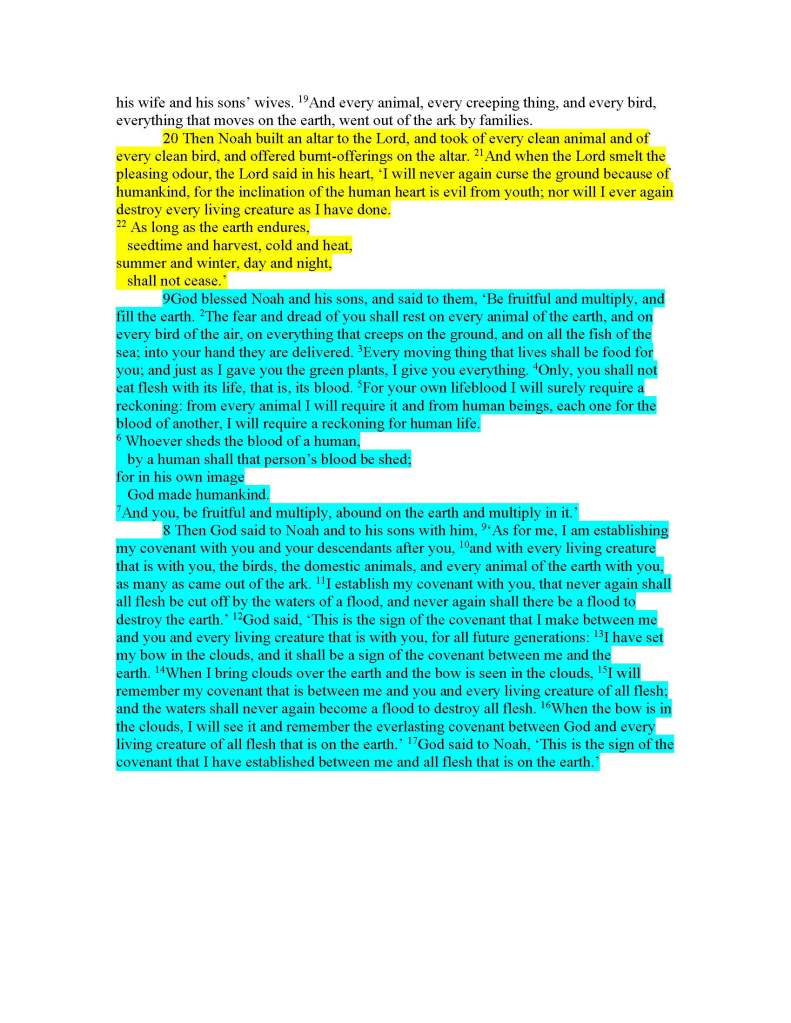

While we’re at it, you may have noticed that a lot of these highlighted verses come at the beginning of a speech. Go ahead and highlight each speech in the appropriate color, depending on whether God or the Lord is speaking. Here’s my version:

Okay, the beginning and the end of this passage divide up very clearly, don’t they? There is a speech by each of God and the Lord at both ends. But the stuff in the middle, with all the dates—there’s not much there, is there? Just a few clear passages.

Now we have to go to stage 2 of the experiment. The question is, can the actual narrative about the Flood be divided up like the speeches? Let’s formulate a hypothesis. This whole story is about Noah and the ark, and there are a lot of words that appear throughout the whole passage, including the speeches of both “God” and “the Lord”: ark, waters, animals. Makes sense. One topic, one vocabulary. But what if both “God” and “the Lord” have phrases that only appear in one or the other, but never in both? If we could then find these phrases in the narrative, we’d be able to figure out whether a verse went with “God” or “the Lord.”

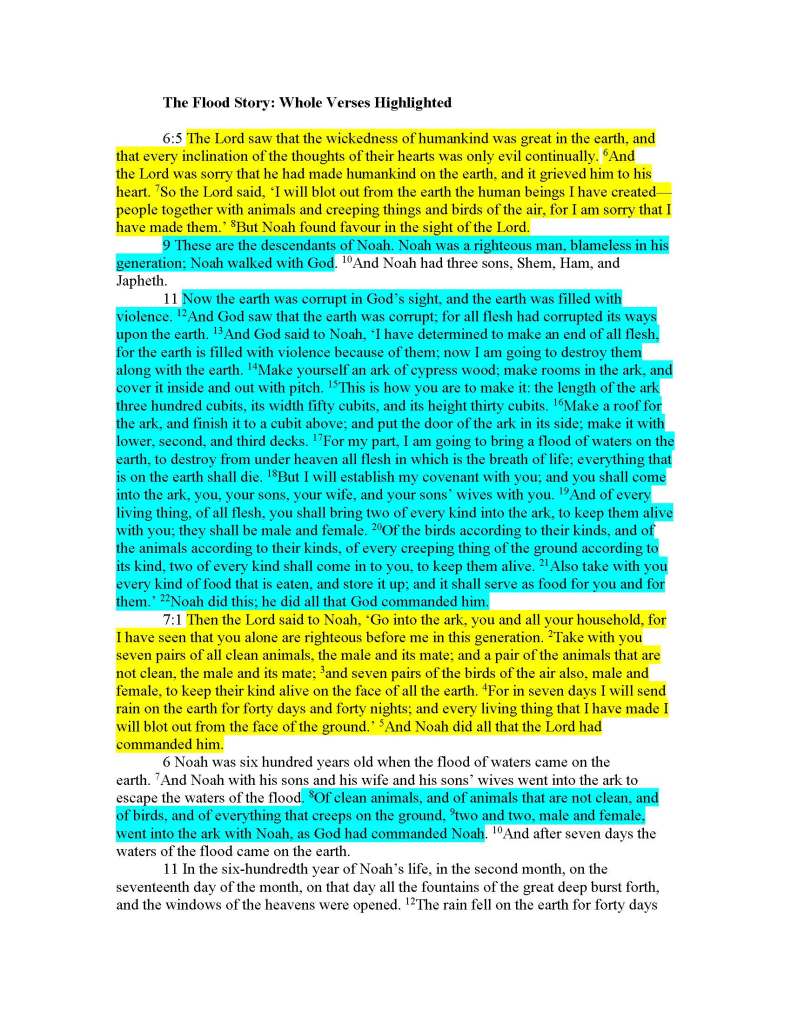

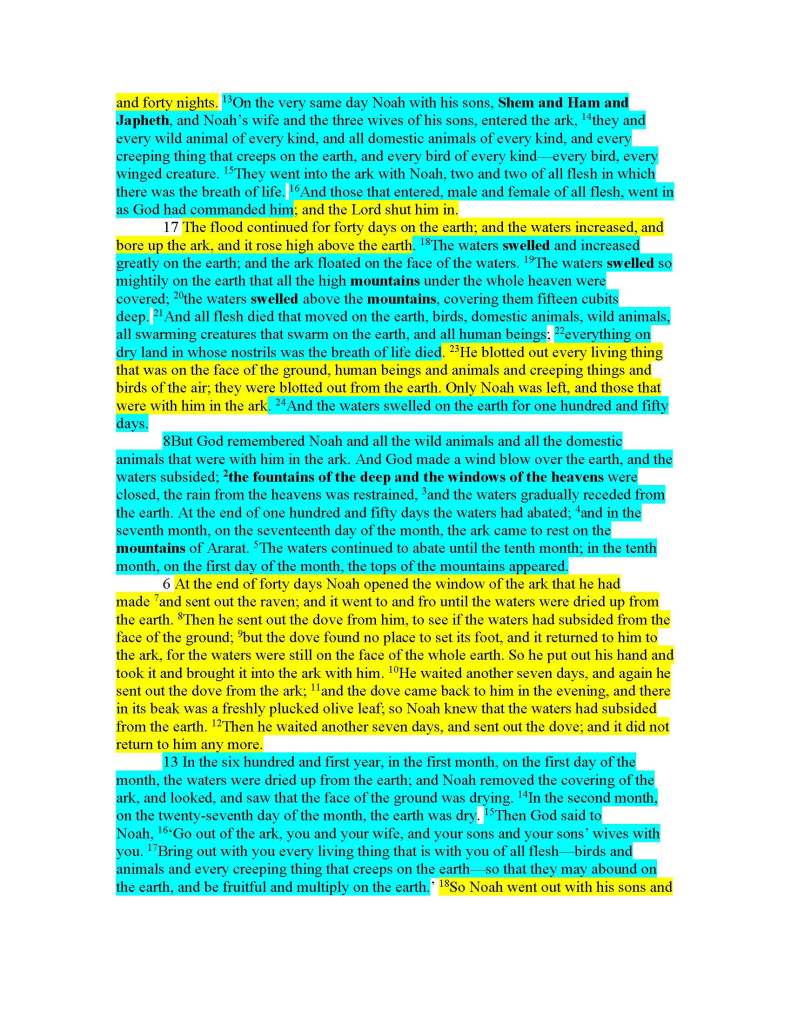

This is easier, obviously, if you’ve got an electronic version of the passage, but a little patient reading will work too. For instance, I notice that the “God” speeches love the word “flesh” (Gen. 6:17, 18; 9:4, 11, 15-17). And that word never appears in a speech attributed to “the Lord.” “Flesh” also appears in the narrative at Gen. 7:15-16, 21; 8:17. Maybe it’s a coincidence. But let’s try the experiment: let’s highlight all verses with “flesh” in them in blue, and see if the pattern is meaningful or random.

With the addition of 7:15 to “God,” that makes two times “God” uses the phrase “breath of life,” with none for “the Lord.” So we’ll mark that in blue too.

A phrase “the Lord” loves is “blot out”: The Flood will blot out all life on earth (Gen. 6:7, 7:4). We also find “blot out” in the narrative, at Gen. 7:23. So let’s highlight that yellow.

Next, we can take an obvious one: only “the Lord” says the rain will start in seven days and last for forty days. “God” does not give any timeline beforehand. Seven and forty days are mentioned at Gen. 7:10, 12, 17; 8:6. Let’s highlight them in yellow.

Okay, let’s see where we are:

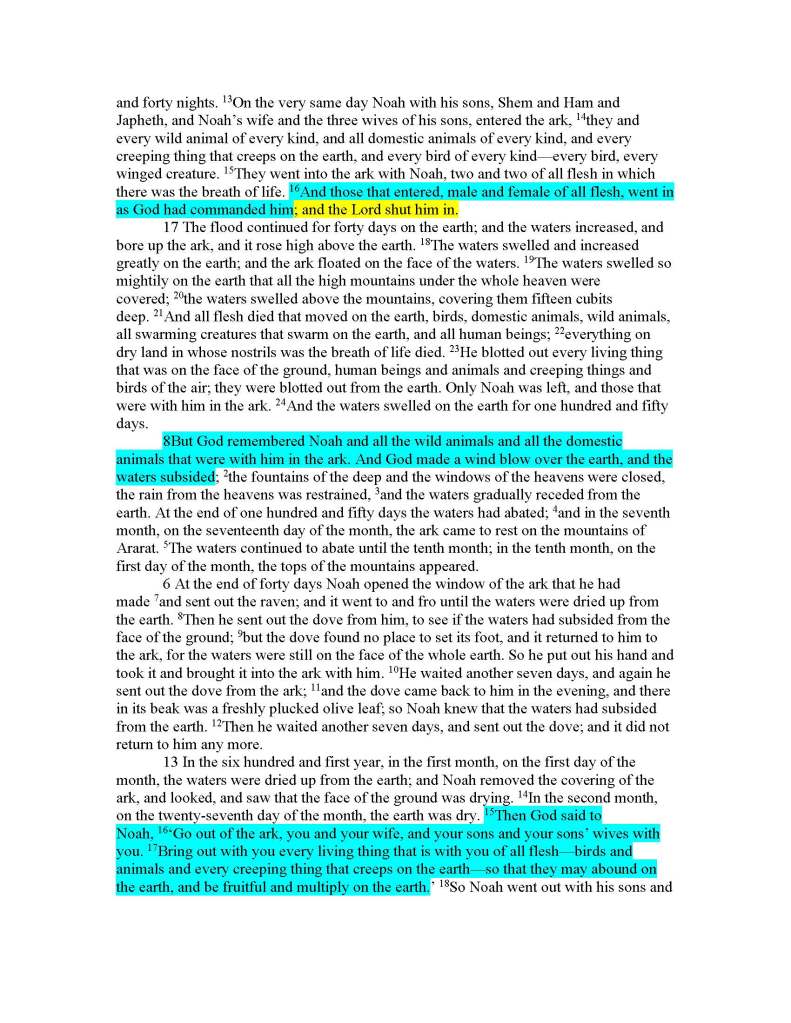

Now the next step: Does assigning all the notices of time that are not to forty days or seven days result in something that makes sense? Since “the Lord” seems to talk about forty days, maybe “God” is responsible for all the other dates. Let’s try it:

Well! That leaves just ten verses. Now we can see if we’ve found any more phrases that are specific to “God.” The phrases “the fountains of the deep” and “the windows of the heavens” occurs in “God’s” verse Gen. 7:11, so when they occur at 8:2, that should be blue too. “God” mentions the mountains of Ararat; let’s try saying the other references to mountains are “God’s” also. This adds the keyword “swell” to “God’s” repertoire, which all together means Gen. 7:18-20 is blue.

We observed that the reference to the flood starting in seven days was “the Lord’s.” In that notice (Gen. 7:10), the phrase “waters of the flood” occurs; we find it only one other time, in one of the two notices that Noah and his family are entering the ark (Gen. 7:7). This means that the other notice that Noah is entering the ark (and notice that there is another!) must be “God’s.” In that verse (Gen. 7:13, plus 7:14 which completes the sentence), “God” uses the names of Noah’s three sons, so the earlier reference to their names at 6:10 must also be God’s.

That just leaves Gen. 8:18-19, which is the notice that Noah and his family and the animals left the ark. Not only does it not use the names of the sons, but it uses the exact same phrase for the family that we already highlighted in yellow: “his sons and his wife and his sons’ wives.” So these verses must be “the Lord’s.”

That leaves us with this:

So we’ve managed to separate out every verse of the Flood story into one of two versions, “God’s” and “the Lord’s.” The final test is this: if we actually try to read only the yellow text, and then only the blue, do the accounts make sense, or are there huge holes? Here they are, one after the other—not a single word added, deleted or changed. Try it and see:

What do you think? Each one seems pretty complete. I only note two small gaps. In Gen. 7:1, “the Lord” tells Noah to “go into the ark.” That makes it sound like the ark has already been introduced, but that doesn’t happen in “the Lord’s” story prior to this. The second gap is in “God’s” story: the moment when Noah and his family leave the ark is never narrated. It seems like it should happen after Gen. 8:17. That’s it. Aside from these two small issues, both versions read just fine independently, and neither one has any of the problems with the calendar that the combined version has. (Or any of the other problems, like the fact that “the Lord’s” account has Noah take seven pairs of every sacrificial animal, while “God’s” has only one pair of everything. The simple reason? In “the Lord’s” account, Noah performs a sacrifice after the Flood; if he only had one pair of everything, that means any species he sacrificed just became extinct. Triceratops burgers, anyone?)

What this means is that the person who edited these two versions together was perfectly aware of the calendar problem, but—just as with Proverbs 26:4-5—the editor had two authoritative versions which he (probably he, given the patriarchalism of ancient agricultural societies, but we don’t know) felt he had to preserve. He smoothed out the calendar as best he could, as we’ve seen; he leaves no A/Not-A contradictions. Maybe it would have been easier to choose one and leave out the other, but for whatever reason he didn’t feel he could do that (again, just as with Proverbs 26:4-5).

This won’t be the last time we see a biblical author combining texts like this, but there are other sorts of contradictions to look at first. But it’s interesting that the editor had two versions. At best only one could be historically accurate, yet historical accuracy didn’t interest him nearly as much as preserving the maximum amount of the tradition he had before him. This is no way to write objective history, but it just might be a better way to write certain kinds of truth than adhering to the canons of A/Not-A.

Leave a comment