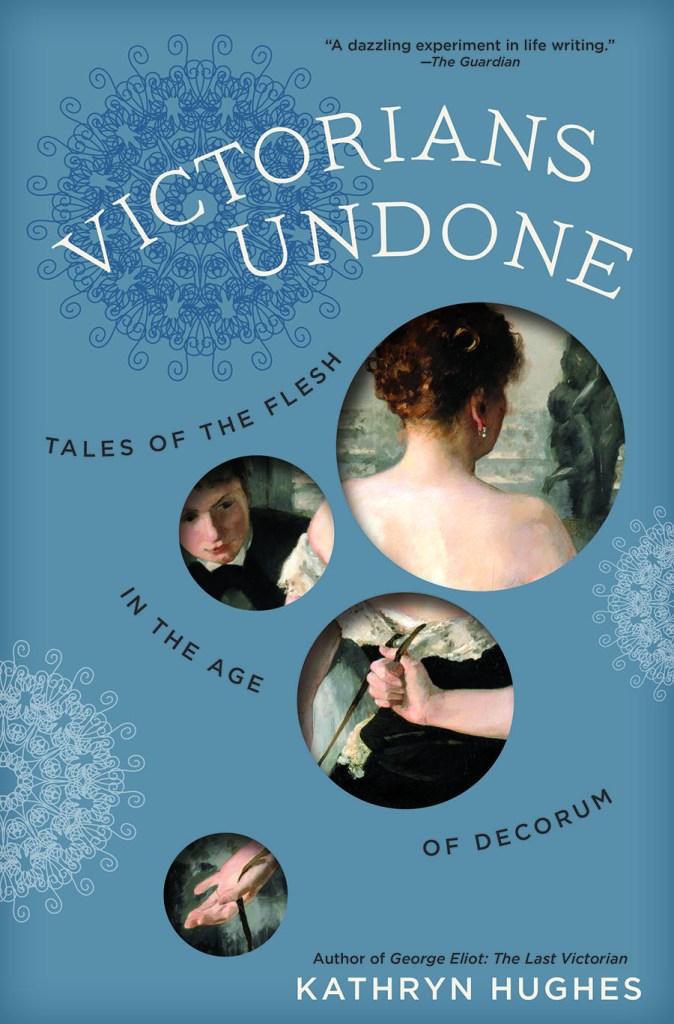

Kathryn Hughes. Victorians Undone: Tales of the Flesh in the Age of Decorum. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 2017.

You probably think you know what this book is about just from the cover and the title. I sure thought I did. Bustles unbustling, and corsets a-popping their whalebones.

Nope. It’s so much better than that. Hughes is focusing on what it was like to have a body in Victorian England, and yes, sex is definitely a part of that. But in terms of time, sex is such a small proportion of what a body does and feels, except perhaps for the very enthusiastic. We spend so much more time being pregnant, wearing a beard, and having hands made either for labor or more delicate things. And Victorians spent a huge amount of that time, much more than we do–and this is the point Hughes is making–being or having those things in public. Having other people make judgments about us and decisions for us based on what they see our bodies doing.

I’m in the middle of researching for a steampunk novel (despite the fact that steampunk’s peak is well past–Ah, c’est la guerre), so I’ve read a lot of stuff about Victorian London, and this is by far the best of all of them. As Hughes observes, there is a tendency in both Victorian and modern biography and history to lose track of the fact that people had bodies to keep alive and in the best state possible given the circumstances, and that these considerations drove many, if not most, of people’s activities during the day. And night. Victorians Undone is a huge corrective to that. Here, bodies swell, itch, carry signs of inconvenient pasts, age, and are even hacked to pieces.

The novelist L.P. Hartley said that “[t]he past is a foreign country; they do things differently there.” Hughes bridges this gap. We all swell and itch and age, and we can feel in our own selves the inconveniences and torments these Victorians felt as Hughes narrates them. Yet the society in which they did all that swelling and itching and aging judged those processes differently than we do, and so, in a real sense, the simple somatic experience of itching is different for us than it was for them. This sense of duality, both in-the-skin proximity and radical distance, is a huge achievement.

If you have any interest in 19th-century England, I require you to read this book. But if you have any interest in history in general, or simply in negotiating society with this weird, leaky, creaking thing we call a body, you’ll see a bold experiment that I hope gets replicated for many times and places.

Leave a comment