Today’s biblical contradiction results from a process much like that which produced the Noah story: two independent versions have been edited together. Unlike the Noah story, the discordances between the two versions are so great that a third voice, the editor’s voice, intrudes to smooth things over.

David is such an important character in the Bible that it’s no surprise that multiple versions of some stories have been preserved. The most famous, of course, is the story of David’s encounter with Goliath in 1 Samuel 17.

The story begins slightly earlier, though, in 1 Samuel 16. The prophet Samuel is tasked with anointing a new king over Israel after the first king, Saul, has failed to measure up to Samuel’s and God’s high standards. Samuel is led to the family of Jesse, and specifically Jesse’s youngest son David. This is the first time David is introduced.

He is introduced a second time at the end of chapter 16, when an “evil spirit from the Lord” afflicts Saul. One of Saul’s nobles recalls seeing a promising young man named David who is good with a lyre. David arrives at court and, whenever Saul is afflicted by the evil spirit, David plays for him and soothes him. While this introduction seems independent of the previous one, there’s no tension between the two, and no reason to think they couldn’t have gone together originally.

Next begins the confrontation with Goliath and the Philistine army. Goliath comes out between the ranks and taunts Israel, and Saul and his army tremble (1 Sam. 17:1-11). Then we’re introduced to David and his family as if we hadn’t just met them all in the last chapter (1 Sam. 17:12-14). A second, redundant introduction is not a contradiction, but it does put us on the alert for a second source. In this part of the account, David is not with Saul, as we were just told at the end of the previous chapter, but is with his father herding sheep. The narrator recognizes the difficulty and hastens to inform us that David has been shuttling back and forth between Saul’s court and his father’s herds (1 Sam. 17:15). Again, not a contradiction; but obviously a weird way of doing things.

Jesse sends David with some food to his three eldest brothers at the battle front (1 Sam. 17:17-22). Goliath is introduced again, as if we’d never heard of him before (1 Sam. 17:23). David and his brothers and the soldiers around him discuss how the king has promised his daughter to the man who kills Goliath (1 Sam. 17:24-30).

Someone overhears David, and tells Saul, and Saul summons the young man. Despite Saul’s misgivings, David boasts of his prowess in fighting wild animals. Saul outfits David with his own armor, but David, unused to such equipment, leaves it behind (1 Sam. 17:31-40). In the middle of the arroyo separating the armies, David and Goliath meet and taunt each other before David summarily dispatches the champion with a sling stone (1 Sam. 17:41-49). The narrator specifically tells us that no sword was in David’s hand–then tells us David took out a sword and beheaded Goliath (1 Sam. 17:50-51). Still not technically a contradiction, but again, a weird way of putting it. The Israelite army defeats and plunders the Philistines (1 Sam. 17:52-54).

Now we finally come to the contradiction: Saul sees David go out against Goliath, and does not recognize him. An obvious possibility is that we should interpret this as an attack of the evil spirit from the Lord, which is generally understood as a form of mental illness. But you can’t use mental illness as a “get out of jail free” card. You need a specific form of mental illness that causes you to not recognize people very familiar to you. Early-onset Alzheimer’s might fit the bill… except that at no point in the rest of the first book of Samuel which details Saul’s further adventures with David does Saul ever display such symptoms again.

There’s another, more telling problem. Saul asks his general Abner who David is, and Abner does not recognize him either (1 Sam. 17:55-56). If you’re used to movie spectacles with casts of thousands, it might seem possible to you that David and Abner have not met. But this is a failure to think concretely about the City of David. It was not a vast metropolis. Some fair images which give a good sense of scale are here: https://blogs.timesofisrael.com/the-importance-of-the-city-of-david/, and here: https://www.generationword.com/jerusalem101/19-city-of-david.html. I make no comment on the commentary that accompanies these images, beyond noting that neither would feel comfortable with my analysis here.

The royal precinct is at the north (to the upper right of any of these images), and a glance makes it clear that every man who had access to that precinct must have known every other man by face and name. There simply isn’t room for enough people for there to be strangers. If Abner doesn’t recognize David here, it must be because Abner has never seen him before either.

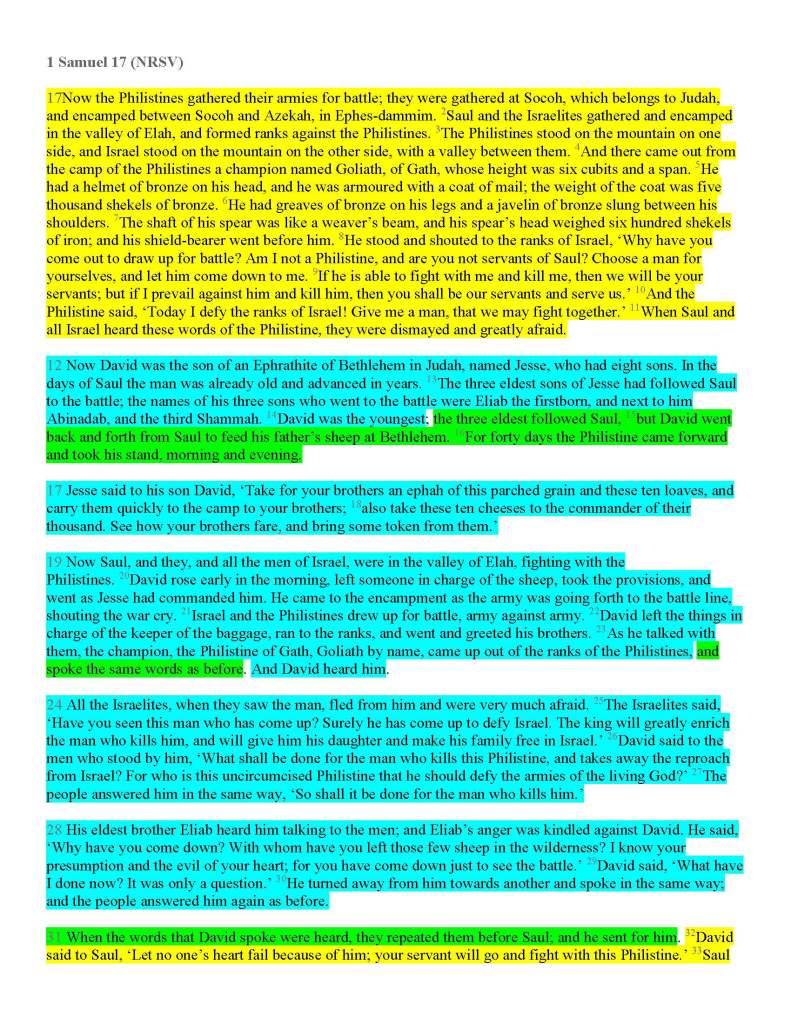

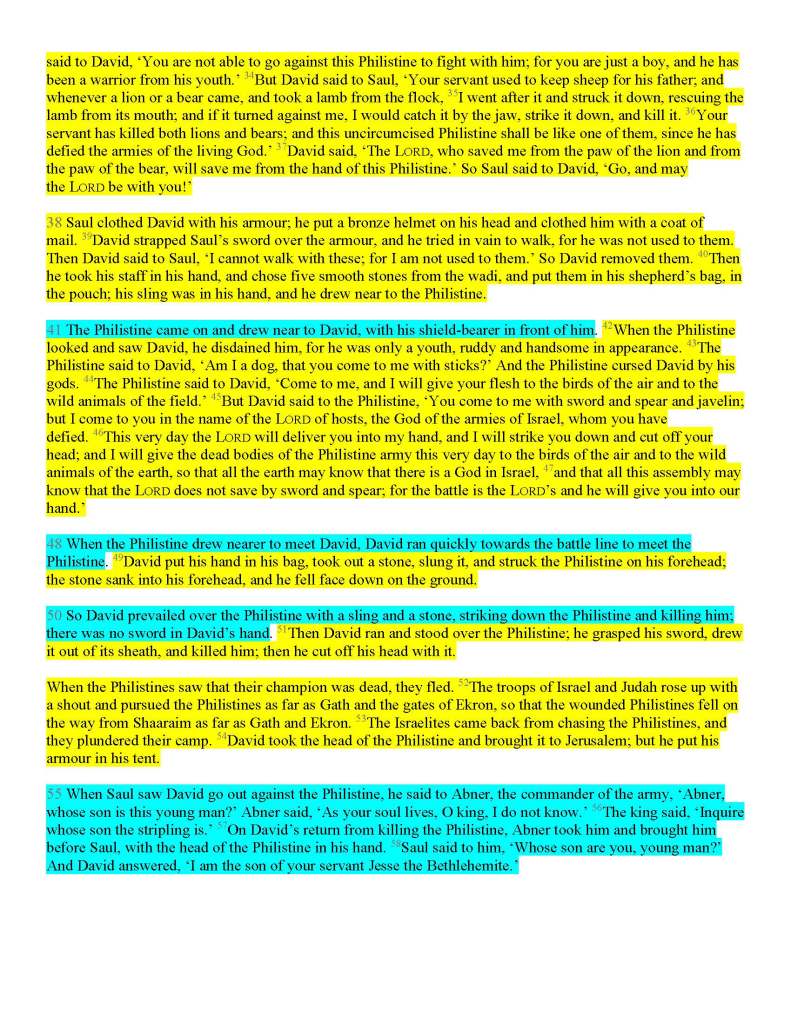

This, combined with the double introductions of David, his eldest three brothers, and Goliath, makes it clear that once again we have two versions of the story combined here. One is the story of a confident but unproven young man; the other is closer to a fairy tale. The first begins back in 1 Sam. 16; the second begins at 1 Sam. 17:12. One features a dialogue with Saul before the combat; the second has David simply march out on hearing of the promises made to the one who defeats Saul. Here they are, with each verse marked for each version. Yellow is the version that begins back in chapter 16; blue is the second version added to that; and the three instances of green are places where the editor needed to smooth things out, since the two versions differ on the crucial point of whether Saul meets David before or after the combat.

Most importantly, the editor needed to make clear how David could be with Saul in chapter 16, and with his father in chapter 17; and then how he came to be with Saul again at verse 32. Separating out the stories removes these difficulties, which makes it clear that the green text is editorial. Both versions now read perfectly well independently. Go ahead, try it:

So there are two stories of Goliath preserved in this version. Once again, the biblical editors felt the need to keep both. In the case of the Flood story, the editor was brilliantly able to combine the tales in such a way that there was no necessary contradiction between the two versions. Here, that was not possible, and so the editor stepped in to clarify matters, but could not smooth over all difficulties. The interesting thing in passages like this is the impulse to preserve both versions, but only as if they were really one version. It’s an impulse we’ll see again in the Hebrew Bible.

One last point deserves notice. There is actually a third version of the Goliath story preserved in the Bible:

19Then there was another battle with the Philistines at Gob; and Elhanan son of Jaare-oregim, the Bethlehemite, killed Goliath the Gittite, the shaft of whose spear was like a weaver’s beam. (2 Sam. 21:19, NRSV)

There have been ingenious attempts to identify Elhanan as another name for David; the problem is that this occurs two verses after David is nearly killed in a battle, and his men insist he no longer go out to battle with them (1 Sam. 21:17). Further, this verse occurs in a collection of brief notices about the heroics of David’s companions; the only reason to try to find David in Elhanan is to avoid the contradiction.

Do we have to make a choice here? In this case, there’s no ethical mandate that results from choosing one or the other, as there was in the contradiction about women speaking in church. I think that in cases like this, we can simply accept that the tradition is multiple. And that’s what he have: a tradition. Traditions are messy and contain weird elements. (Easter eggs? Chocolate bunnies?) A history that contains a contradiction is simply incoherent. A tradition that contains a contradiction is something that has grown organically, with only occasional pruning, into riotous life and color. Often its left hand doesn’t know what its right hand is doing. I can relate.

Stuff I Read:

P. Kyle McCarter, Jr. I Samuel (The Anchor Bible). (Garden City, NY: Doubleday & Co., 1980).

Leave a comment