Today’s biblical contradiction comes from the Joseph story in Genesis. It’s a tale of enslavement and dreams of freedom, but it begins with a contradiction that’s practically hallucinatory. The passage we’re looking at is Genesis 37:18-36, 39:1.

Joseph is the youngest of Jacob/Israel’s sons, and he has dreams that all his family will bow down to him. Needless to say, Joseph’s eleven brothers do not take this well. While the brothers are out pasturing the flock, their father sends Joseph to find out how they’re doing. You just know the brothers will react to that with dignity and maturity. So they do the only thing they can do under the circumstances: they decide to kill him.

Reuben, the eldest, tries to save Joseph by proposing they throw him in a pit, presumably to die of exposure or dehydration since there’s no water in the pit. Reuben secretly intends to save Joseph later. The brothers agree to the plan, strip off Joseph’s wonderful coat, and toss him in.

Then they sit down to eat, with all the remorse of Hannibal Lecter. A caravan of Ishmaelite merchants (the Ishmaelites lived in Arabia), and Judah has a bright idea: “Let’s sell him to the Ishmaelites! At least that way we get some cash.” The brothers think this, too, is a great idea.

You would expect the next sentence to read, “Then the brothers pulled Joseph out of the pit and sold him to the Ishmaelites.” But that’s not what happens. Gen. 37:28 reads:

“Some men, Midianites, merchants, passed by, and they pulled, and they brought Joseph up from the pit. They sold Joseph to the Ishmaelites for 20 pieces of silver. They brought Joseph to Egypt.”

I give my very literal, choppy translation above for a reason which will become evident. For now, the sense seems clear: Some Midianites (Midian is a territory in the general area of the Sinai Peninsula) have intercepted Joseph and sold him themselves to the Midianites. Where exactly the brothers were while this was happening is not at all clear. But let’s go on.

Reuben returns to the pit, sees Joseph is gone, and freaks out. He returns to his brothers (who evidently were somewhere other than the pit’s edge) and together they decide to rip up Joseph’s wonderful shirt, dip it in goat blood, and tell their father that Joseph was killed by a wild animal. The old man falls for it. Meanwhile, the Midianites sell Joseph to Potiphar, one of Pharaoh’s courtiers, in Egypt.

Wait, what?

Gen 37:28 clearly said the Midianites sold Joseph to the Ishmaelites. How can they still have him here at Gen. 37:36? And it gets weirder. After another story about Jacob/Israel’s older sons in chapter 38, Gen. 39:1 returns to Joseph’s story–where he is sold to Potiphar by the Ishmaelites! Unless Potiphar is an extraordinarily bad businessman, how could he have bought one child twice from two groups of people?

After the stories of Noah and the Flood, and of David and Goliath, you might be able to predict what’s going to happen next. This story is in fact two stories combined, interweaving verse by verse. We can separate them through narrative logic, by seeing what goes together. We begin with the fact that there are two endings to the story: one with the Ishmaelites, and one with the Midianites. So there has to be one story where only the Ishmaelites are present, and a second with only the Midianites.

Once again, Gen 37:28 is key. It says the Midianites sold Joseph to the Ishmaelites. Somehow, that must not be true. Let’s look at that verse again:

“Some men, Midianites, merchants, passed by, and they pulled, and they brought Joseph up from the pit. They sold Joseph to the Ishmaelites for 20 pieces of silver. They brought Joseph to Egypt.”

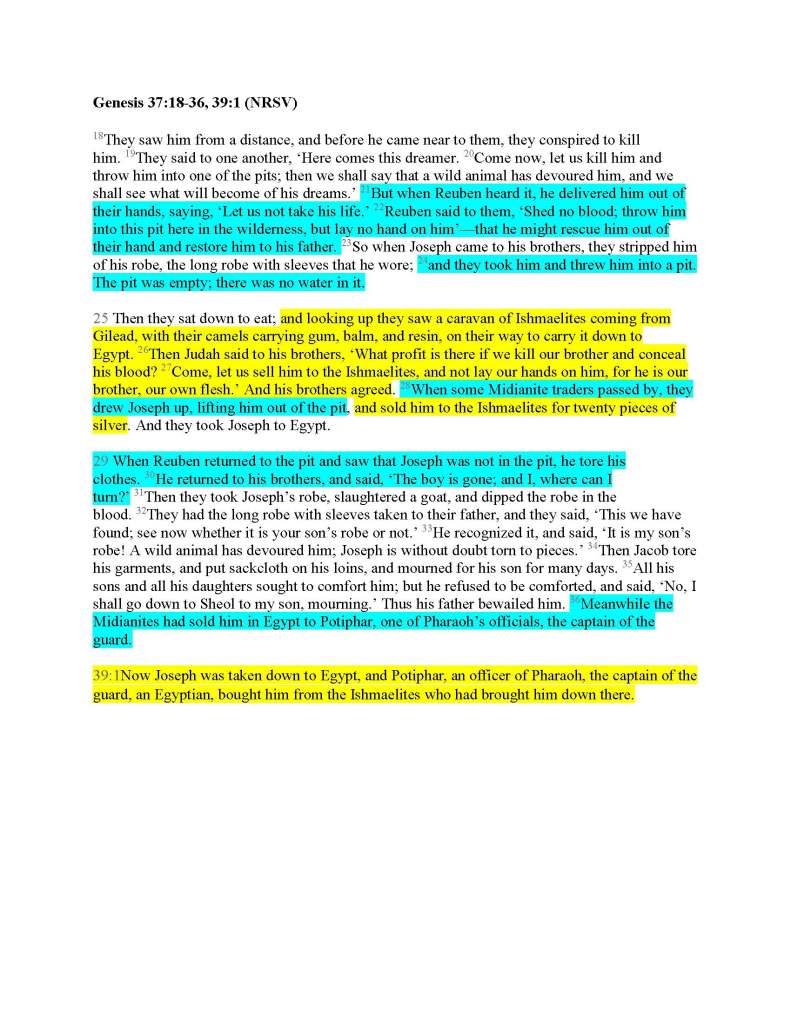

Note how I’ve put a period after “up from the pit.” The subject of the sentence that follows is “they.” In context, the antecedent of that pronoun is “Midianites.” But what if the Midianites (v.28a) are not part of the same story as “they” in v. 28b? Let’s see what that does us. I’ll use yellow for my hypothetical Story A (featuring the Ishmaelites) and blue for Story B (featuring the Midianites). We can also color in all references to both groups.

That solves the problem of how to get Joseph to Potiphar in the hands of the Midianites and the Ishmaelites. But this only works if we can make two coherent stories out of this passage. Next, I note that the pit only occurs in Story B. So let’s color all the verses referring to the pit, and the consequent tearing of Joseph’s shirt, in blue. This gives us the following:

Now, verses 18-20 have a redundancy: In v. 18, the brothers’ conspiracy is merely narrated, while in vv. 19-20 the conspirators actually speak. Either verse could easily follow immediately after Gen. 37:17, when Joseph finds his brothers. It would be simple to split these up and assign one passage to Story A and the other to Story B. But which is which?

Since v. 20 refers to the pits, we might be tempted to assign this to Story B, but actually, this makes no sense because in v. 20 the plan is to kill Joseph and throw his corpse into a pit. Reuben’s intervention, which is obviously trying to be sneaky given his intent to come back and save Joseph, would not work. Since the brothers are intent on the boy’s murder, why would they agree to this? Reuben’s plan only works if it seems like a method for murder, not a reduction in severity of the brothers’ intent. So vv. 19-20 are Story A, and v. 18 is Story B. Finally, in Story A the plan involves a lie about a wild animal, and this is fulfilled by vv. 31-35, which thus also belong to Story A.

That leaves only vv. 23 and 25a, and the last words of v. 28. V. 25a, “Then they sat down to eat,” would explain why the brothers left the pit, so this is blue. The long-sleeved coat is a part of Story A, so that’s yellow. And since Gen. 39:1 has a reference to the Ishmaelites taking Joseph to Egypt, we need one for the Midianites–and here it is at the end of v. 28.

So here we are:

Both versions read very cleanly (go ahead, try it)–but not perfectly cleanly. First, in the verses before this passage (Gen. 37:12-17), there is only one account of Joseph traveling to meet his brothers, and because it has the dreams and the long-sleeved coat, it goes with Story A. There is no remnant of Story B’s version of Joseph’s long walk. Second, Reuben’s story in Story B seems to end very suddenly. Maybe this is a personal reaction, but it feels to me like there should be some response on the part of the brothers to Reuben’s anguished “Where shall I turn?” Perhaps both of these gaps in Story B result from Story B having passages that would openly contradict something in Story A, and so those parts were left out.

That begs the question, though: Why would editors combine two versions of a story very carefully, keeping all that they could, but then still edit out some passages when the contradictions became too pressing? If they were going to edit stuff out any way, why bother to keep any of it?

We’ll get a chance to reflect on these questions, which are at the heart of scholarship on the Torah, soon. But first, there’s one more time in the Bible that two sources are combined like this. And we’ll talk about that next week.

Leave a comment