If you’re getting tired of color-coded chapters of the Bible, I have good news: this is the last one we’ll do. There are very few other passages where two sources have been interwoven verse by verse (the parting of the Re(e)d Sea is one), and all of them are accomplished so artfully that they do not produce contradictions. There are plenty of other places where two sources have been put together, but these occur on a paragraph-by-paragraph, or even chapter-by-chapter, basis and so, again, have little in the way of outright contradictions.

Today’s story comes from the book of Numbers, and concerns one or two revolts against Moses in the wilderness between Sinai and Canaan. It’s a good one to end the color-coding with, because it shows both the textual problems this sort of combination can create, and the limits of what we can reconstruct about the original sources. In the stories of Noah and Joseph, we could separate the sources without anything left over; in the story of David and Goliath, there was a clear but sparing editorial hand in the text. Numbers 16:1-35 is closer to Goliath than Noah, and appears to go even further in terms of editorial intervention.

The story begins with four men, Korah, Dathan, Abiram and On, rebelling against Moses’s authority. Moses responds by commanding the Korah and the rest of the rebels to prepare incense for worshipping God, and bring it to the tent. Moses then summons Dathan and Abiram… but wait. Why are they separated? Indeed, these two men say they will not come to Moses, even though we thought Moses was just talking to them with Korah. In fact, Moses addresses Korah again, giving further directions for the incense offering, and never mentioning Dathan, Abiram or On.

Then Moses gets up and goes to Dathan and Abiram himself and tells the rest of the Israelites that if Moses has been chosen as God’s prophet, then the earth will swallow up Dathan and Abiram. The ground indeed opens up. And then, after they’ve been swallowed up, fire comes from God and incinerates the rebels, which seems, quite literally, overkill.

So at the beginning four men are mentioned. On never appears in the rest of the story, a fact we’ll return to below. Sometimes Korah appears alone; sometimes Dathan and Abiram appear with no one else, but never separately; and sometimes Korah, Dathan and Abiram appear together.

There are two complaints against Moses in this passage. The first (16:3-4), immediately before a response that only addresses Korah and his company, argues that Moses and Aaron are not the only holy people in Israel–that, indeed, all Israel is holy, and can serve as priests. All references to “you” in this passage are plural: Moses and Aaron. The second (16:12-14), by Dathan and Abiram, complains only of Moses–all references to “you” are singular–and accuses him of acting as a despot (tistarer). Moses’s responses to each of these speeches, in turn, either reference Aaron (when talking to Korah) or do not (when talking to Dathan and Abiram).

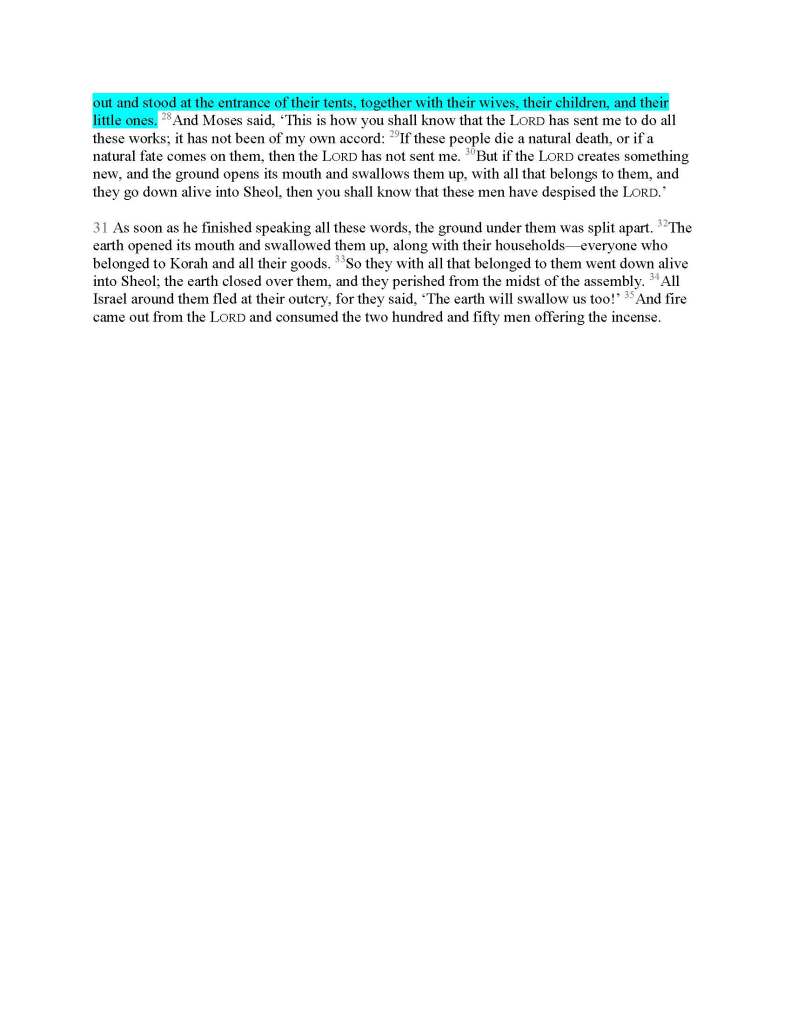

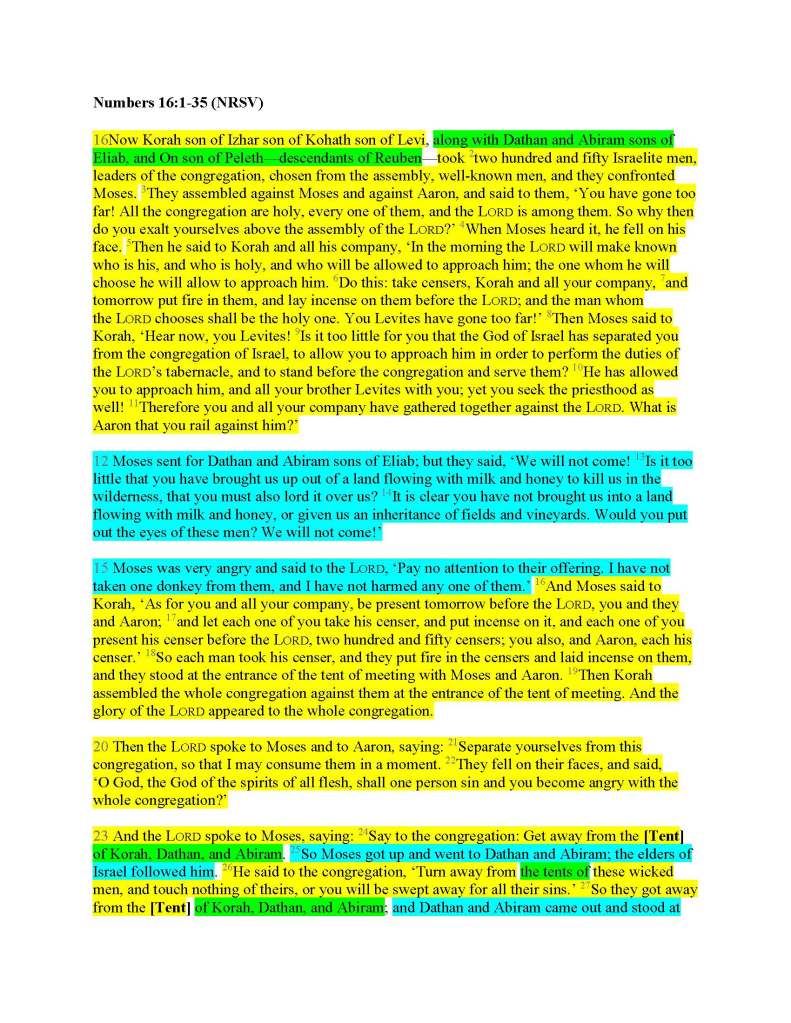

Let’s start by isolating the passages which deal either with Korah alone and Moses and Aaron together (yellow), or with Dathan and Abiram together and Moses alone (blue).

That leaves only the beginning and the end to figure out. To start with the beginning, we can note that Korah and his people “assemble against” Moses (16:3), while Dathan and Abiram pointedly do not (16:12). Verses 1-2 speak clearly of an assembly, so the bases of these verses is Story A in yellow. What’s left is not a sentence, and when two sources have been combined, they almost always leave full sentences. That means the remnant of vv. 1-2 is from an editor’s hand. There’s further evidence for this in the Hebrew, where the verb for which Korah is the subject is vayyiqach, “He took.” In Hebrew, as in English, “to take” is a transitive verb, but in the syntax of the sentence is seems to mean “he betook himself,” which is not otherwise attested in the Bible. The object of the verb occurs at the beginning of v. 2, the 250 Israelites, now separated by the editor’s intervention. We’ll highlight it in green.

Turning the ending, we see at the very end (v. 35) that Moses’s instruction to Korah has been carried out, and the 250 men have offered incense and been killed. So clearly that’s yellow. Looking at v. 28, Moses is speaking alone and only about himself, not Aaron, so the threat to be swallowed by the earth should be blue. But there’s a problem: the fulfillment verses specifically reference Korah! However, that phrase can be separated without harming the sense of the rest of the passage, so that once again we may suppose an editor’s hand.

Finally, in vv. 23-27, “Korah, Dathan and Abiram” are all mentioned together. If we’re right about the sources, either “Korah” or “Dathan and Abiram” is editorial. The essential point to notice is that we are standing at someone’s tent. Korah has been summoned to the entrance to the Tent of Meeting, which is on the east side of the Tent (Numbers 2:3). Korah’s grandfather Kohath’s clan was stationed on the south side of the Tent (Numbers 3:29). So we are nowhere near Korah’s tent.

Another thing: In vv. 24 and 27, where the NRSV has “So they got away from the dwellings of Korah, Dathan and Abiram,” the Hebrew for dwelling is singular: mishkan, “tent.” More to the point, this is specific word for the Tent of Meeting, as opposed to an ordinary tent, which is an ohel, as in v. 26. I propose that God in the original source told the Israelites to get away from the Tent of Meeting; an editor has come in and added “of Korah, Dathan and Abiram” in an attempt to tie the two sources together. In v. 26, the same editor has added “the tents of” for the same purpose, where the original read, “Turn away from these wicked men…” I’ll replace NRSV’s “dwellings” in these two places with “Tent.” So the final division is this:

So we see here a more active editor than anywhere else we’ve looked. This raises the question of the limits of this sort of analysis. In other passages, we’ve seen places were text appears to have been deleted because it presented insuperable challenges in avoiding outright contradiction. This passage appears to have been especially problematic, since the two stories have significantly different casts of characters. Here, it may be that the introduction to the story of Dathan and Abiram–the occasion on which Moses called for them in the first place–has been lost. Still, most of each story seems to have survived. And perhaps that would not have been the case if, say someone had copied each original source onto its own scroll. At some point, someone might have felt the need to choose one or the other. Thanks to the combination of the sources, we have more story than we might have otherwise, contradictions and all.

Or do we? What happened to On? Was there a third story of rebellion in the wilderness, now only survived by this mysterious figure? What was the point of mentioning him, only to abandon him?

To discuss this, we’ll need to look next week at a stimulating book by an old professor of mine, Joel Baden. ‘Til then!

Leave a comment