Ray Bradbury was once asked what his favorite topics were. He immediately said, “Dinosaurs!” A moment later, “Egypt! Mummies!” When a seven-year-old version of me read this, he had to agree that Bradbury had put his finger on one and two. Today, my list would probably be more complicated, but these would still be top five.

In researching a story about Egypt (details forthcoming), I came upon this book by Rune Nyord. I had a clear sense of what the Book of Going Forth by Day was (vulgarly known as the Book of the Dead): an instruction manual for the Egyptian afterlife, telling the departed soul how to pass the trials of the afterlife. This has been the consensus since the late nineteenth century. Nyord’s argument is that this is fundamentally wrong.

Here’s the reason. The consensus understanding of Egyptian afterlife beliefs was not built on objective readings of the indigenous material following Champollion’s decipherment of hieroglyphs in 1822. Instead, the main components were beliefs about the reason for mummification, Masonic initiation rites and Protestant theological doctrines concerning individual judgment. It was built up through the early modern period by people who could not read the texts, and was not discarded when reading Books of Going Forth by Day became possible again.

As to mummification, Nyord says that scholars observed that the process caused the long-term preservation of the prepared body, and they assumed that therefore this preservation must have been the primary, or indeed the only, intended purpose of making a mummy. Initiation rites popular among European elites of the time led to seeing the Books of Going Forth by Day as a linear process of undergoing trials. And Protestant theology led to positing the scene in chapter 125 (chapter numbers are based on E.A.W. Budge’s 1895 edition, incorporating several different Books) of the weighing of the heart against a feather as the centerpiece of the text. None of these assumptions, Nyord says, is justified.

Unfortunately, Nyord only intimates what should replace these structures of thought, saving that for another book. The hint he drops is the proposal that mummification and the Books are not about an individual’s experience of the afterlife; they are about turning a dead relative into an ancestor, a supernatural being that can aid the family on an ongoing basis. It’s a fascinating suggestion, but even if true, it seems plausible that the rituals of the Egyptian dead could be both a rite to turn a corpse into a divine being, and a description of the subjective experience of that being.

With that in mind, I decided to reread the Book of Going Forth by Day, see if it made sense to read it as Nyord suggests. To try to give myself a more concrete data set, instead of reading Budge’s condensation of several Books, I found an edition of a single Book, that of a man named Sobekmose, translated by Paul O’Rourke. O’Rourke in his introduction reads the papyrus as I suggested above—as both an account of an individual afterlife, and as an instrument in the creation of a supernatural ancestor. We’ll see if that hypothesis holds up.

The first thing I notice in the first short spells that are completely preserved has been noticed by many readers of Books before me: that Sobekmose is called “justified” from the very beginning. At a minimum, then, the Book is non-linear, if it does record an individual experience; it presumes the success of its own process. As a collection of spells, then, Sobekmose’s Book is more like an anthology than a novel. This doesn’t determine how to read it; in fact, it leaves all possibilities open at this point. There’s no reason to expect from the Egyptian texts something like Dante’s strict progession.

The sixth spell in the Book is numbered chapter 10. (I number spells by the presence of a rubric beginning the passage that indicates its purpose and occasion.) The one before it is chapter 76, and the one after it is chapter 22. This is because Books of Going Forth by Day only acquired a set order in the Late Period, around 600 BCE, while Sobekmose’s Book is from the New Kingdom, around 1500 BCE—again indicating its nature as an anthology. In addition, the sixth spell finds Sobekmose claiming that he is “a god, lord of the Duat” and claiming powers not only like gods but over gods. Other spells will find similar claims, such as the 13th spell (chapters 96/97), where the justified dead person (called for the first time an akh, a divine ancestor) claims to be above all the other gods. If every Book gives every akh such power (and they do), one wonders what happens when two akhs disagree about what to do. Does consensus arise naturally among the dead, or is it chaos? The Book never wonders about these things. If the purpose is to turn a corpse into an ancestor, it doesn’t need to, because the point is to claim all possible power for one’s own ancestor. What other people claim for their ancestors is of no account.

The eighth to tenth spells give Sobekmose the power to turn into animals: a swallow, a snake and a crocodile. While these might be handy powers under certain circumstances (as O’Rourke observes), the Book never mentions an occasion on which it would be necessary to use them. On the other hand, having these powers means that any time his family sees a swallow, a snake or a crocodile, they could see it as their ancestor watching over them.

The 19th spell (chapter 153) is the first one where Sobekmose must know the identities of certain magical objects, here, parts of the solar boat. It is often alleged that if the dead person does not know the correct names, they are doomed to one of a variety of unpleasant fates. There are two problems here. One is that there is no intimation of what would happen if Sobekmose did not know the names. Rather, once again, the Book assumes that Sobekmose is already an akh, already powerful and full of knowledge.

Second, there is the problem, rarely addressed, of what ordinary Egyptians thought of the afterlife. This is a problem of data, as the poor had little influence on their postmortem fate. For instance, stonecutters at Amarna were buried in mass graves. Herodotus, writing of Late Period Egypt, says there were three levels of mummification based on cost, the lowest-cost method being an enema and a 70-day bath in natron salts (Histories 2.88). We can’t take Herodotus on his word about Egyptian matters (he may have had his information secondhand or worse), but if at all true, it indicates that some kind of embalming was important even to such lower-class people as could still afford some such procedure. However, a Book of Going Forth by Day would only be available to the wealthiest. The Book, again, seems to be an assurance of a thing that is already accomplished: a status symbol, not an essential piece of equipment suited to a task. Sobekmose will occupy a privileged place in the afterlife—living in a better neighborhood, as it were—as compared to those who do not have one.

The 26th spell (chapter 149) is a journey past 14 mounds. Here, at last, we do have monsters in the mounds that pose a threat to akhs, the sort of thing we would expect in an individual account of an afterlife. Indeed, these other akhs are said to keep their distance from the mounds. However, they pose no threat to Sobekmose, who orders them around like flunkies. This again indicates Sobekmose’s privileged place and power: not every akh will get to visit the 14 mounds and not die a second time, but the monsters pose no threat to him.

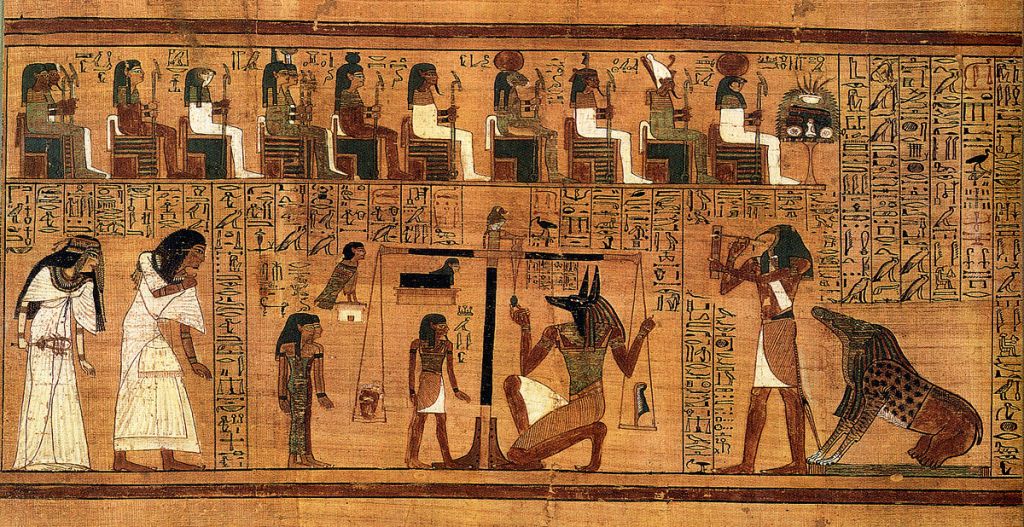

The 28th spell is the famous chapter 125. First, Sobekmose’s scroll contains no weighing of the heart; indeed, in Budge’s edition, none of the three Books cited contains the scene in a narrative form, but only in illustration. The weighing of the heart may have been massively overstated in its importance to the Egyptian afterlife. In any event, this spell begins with the “negative confession”: “I have not done anything evil…. I have not deprived the orphan…. I have not caused pain…. I have not acted lasciviously….” The ancient Egyptians, of course, were not stupid. They were perfectly aware that some people who were provided with Books of Going Forth by Day had done these things, and worse. They knew them by name. The scribe who wrote their Book knew it as he gave the Book to the family. How did they reconcile these facts? The Book gives no explicit indication.

The 32nd spell (chapter 17 part 3) appears to be one of several groups of challenges and responses, where the akh must know what to say and when. There are two interesting things about this chapter. The first is that we have no idea who is offering the challenge, whereas previously the challengers were always made clear (the parts of a boat, the 42 gods at the negative confession, the parts of a doorway). The challenges here erupt from the text itself, and subside back into it. The second is that it is full of variants: places where the text offers two or even three possible responses to a challenge. As usual, there is no narration of what would happen if Sobekmose failed a challenge, but the variants seem to entail this happening, and provide backup. It’s a peculiar way to imagine an individual afterlife, as there is no mise-en-scène in this chapter, but it reflects an understandable precaution on the part of the scribe who is producing a text that is instrumental in the transformation into an akh.

The 37th spell (chapter 27; similarly, 30A) introduces a new idea: that a person’s heart can oppose the akh precisely by saying what that person has done. This seems to answer how a wicked person could pass the negative confession, by suppressing the true witness of his heart: “Do not reproach this heart of mine. It shall not say what I have done…. Obey me, my heart. I am your lord.” Is the heart trying to tell the truth against Sobekmose?

The 55th spell (chapter 105 II) says, “This evil utterance which I have said (and) this evil impurity which I have done will not be put on me because this papyrus amulet that belongs at the throat of Re… belongs to me.” This, for the first time, clearly moves beyond presuming success and shows the scribe acting effectively through his production of the Book for the benefit of Sobekmose, regardless of the dead man’s deeds in life. It is an exalted view of the scribe, making his work all the more valuable for the family. It is they who will bury it along with Sobekmose in his tomb, and though they will never see it again—and perhaps never read it at all—it is for their benefit, to help them see their dead relative as an efficacious ancestor. Yet it functions as an amulet, as an object of power, not as a text the family will read, and so maybe not as a description of what anyone thinks will actually happen to Sobekmose.

Indeed, the only person to whom the actual words of a Book of Going Forth by Day matter may be the scribe that writes it, and it may be his perspective we should focus on as he constructs this amulet—a text whose only audience is also its author. How does he see his task? Is he filling out a form letter, or does he feel invested with awesome, heavens-shaking power? If we could answer that question, I think we would understand the Book better. After all, though Sobekmose often says in the Book that he knows the spells, it is of course the scribe who really knows them.

There may be some confirmation of this perspective in the ending of the 75th spell (chapter 1), almost at the end of the Book. The spell ends with the first reference in the body of a spell (as opposed to the ubiquitous rubrics that begin the spells) to Sobekmose in the third person: “This Goldworker of Amun Sobekmose, justified, has set out here. No fault of his was found therein. The balance-scale is free of his faults.” Spells 83 and 84 (chapters 2 and 3) similarly speak of Sobekmose in the third person, and it is the scribe who is speaking.

In the 78th spell (chapter 94), there is even a self-portrait of the scribe, speaking in the voice of Sobekmose. “Bring a water pot to me. Bring a palette to me with these writing materials of Thoth, the secrets which are in them (belonging to) the gods. See, I am a scribe…. I shall do what is right so that I shall go to Re every day.” There is no reason to suppose that the earthly Sobekmose knew how to write, as his profession was a goldsmith. Once again, we see the role of the scribe exalted, even divinized.

For the family who wants their relative to become an ancestor, then, the Book of Going Forth by Day is an amulet. It matters little what is actually written in the scroll, though a certain weightiness is obviously expected. It is possible to imagine scribes committing a massive fraud on the bereaved; yet the scrolls reflect a great deal of care on the scribes’ part. Perhaps there was a way of checking their work. Or perhaps the scribes took copying and arranging these spells with deadly seriousness. It seems likely that the Books tell us something important about scribal beliefs about their own afterlives. What they have to say about what non-literate elite Egyptians may be much more restricted. We’ll have to wait some years for Nyord’s next book to see what comes next for Egypt and its mummies.

Works Consulted:

Ernest Alfred Wallis Budge, The Egyptian Book of the Dead (New York: Penguin, 2008 [1899]).

Rune Nyord, Yearning for Immortality: The European Invention of the Egyptian Afterlife (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2025).

Paul F. O’Rourke, An Ancient Egyptian Book of the Dead: The Papyrus of Sobekmose (New York: Thames & Hudson, 2016).

Leave a comment